Introduction

State of the Art (SOTA) analyses are the backbone of any technical documentation. Don’t believe it? Let’s put it to the test. Before developing your device, you likely assessed what the medical field needs—congratulations, that’s a SOTA analysis. To market your device competitively, you probably researched what other manufacturers are doing again, SOTA. Struggling to define acceptance criteria for your clinical evaluation? That’s because you need a solid SOTA foundation. Determining the clinical benefit of your device compared to existing treatments? SOTA. Defining meaningful endpoints for clinical studies? SOTA. Identifying device harms, risks, and probabilities for risk management? You guessed it—SOTA. The same applies to Post-Market Surveillance (PMS): if you want to interpret incident data beyond just “3 incidents per 1,000 devices— sounds small,” you need SOTA insights at your fingertips. Which standards are relevant for your device or your company? SOTA analysis. And what about the applicable guidance? SOTA, SOTA, SOTA. no proper guide on how to do it right. This document is here to change that. While the identification of SOTA has gained particular relevance in Europe with the introduction of MDR, the information in this document applies to certification worldwide, not just in the EU. Let’s start. The above examples should make clear that SOTA is not just for clinical evaluation. It is essential for research and development, marketing, sales, risk management, post-market surveillance, and even QMS. Yet, if SOTA is so important, why do so many companies get it wrong? Because, currently, there is no proper guide on how to do it right. This document is here to change that. While the identification of SOTA has gained particular relevance in Europe with the introduction of MDR, the information in this document applies to certification worldwide, not just in the EU. Let’s start.

BOX 1: Search, review, meta-analysis, umbrella review The terms “systematic search” and “systematic review” are not synonymous. A systematic review begins with a systematic search but also includes critical appraisal and a structured synthesis of the evidence, either qualitatively or quantitatively. Systematic reviews that synthesize results quantitatively are called meta-analyses. Finally, umbrella reviews synthesize multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses

You can think of the intended purpose as the underpinning on which the entire technical documentation of your device is built. Therefore, you should create the intended purpose as the very first piece of information in your technical file. Ideally, you should have a first version of the intended purpose before starting any development, verification, or validation activity. Do not expect to get the intended purpose perfect on the first try; you will probably need several rounds of refinement.

The MDR defines “intended purpose” and mentions it 83 time. However, the MDR does not define “intended use” even though it mentions it 16 times. “Intended use” is a terminology that stems from the pharma and from nonEuropean certification systems, including the FDA. IMDRF is aware of the different terminologies and in WG/N9 attempts to make a subtle distinction between the two expressions. However, in WG/N47, IMDRF treats the two terms as equivalent alternatives. In the CE-certification praxis, you can consider the two terms to have the same meaning. This is also the position of MDCG 2020-6.

When creating your intended purpose, you don’t have to start from scratch. There are plenty of resources available to help you draft it. We suggest looking at the nomenclature provided by the GMDN Agency. While the GMDN definitions do not necessarily cover all the information you need in your intended purpose, they often provide a good starting point. Another interesting source is the MeDevIs website from WHO.

1.1 Making clarity on SOTA

Let’s begin our journey into SOTA analyses by addressing some of the most common misconceptions. The confusion often starts with the terminology itself. Many companies refer to SOTA analyses as the literature search, a phrasing that reflects two key misunderstandings.

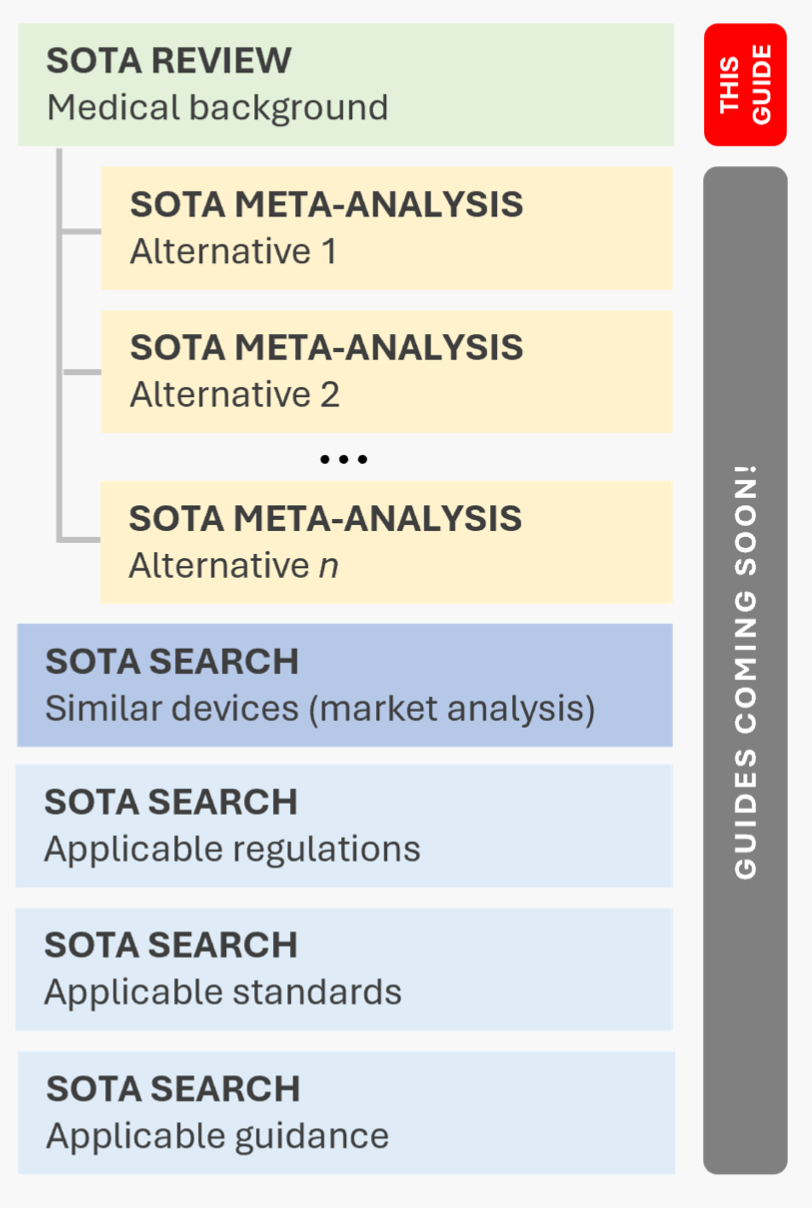

First, most SOTA activities are not merely literature searches. Instead, they take the form of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or umbrella reviews (see Box 1 for an explanation of these terms). This means that SOTA analyses go beyond simply retrieving literature—they involve a structured synthesis, either textual or numerical. Second, a SOTA analysis is not a single, monolithic process. The analysis begins with a systematic review to establish the medical background (the focus of this document). This review is the topic of this document. The analysis then proceeds with meta-analyses to evaluate the performance and safety of medical alternatives (a dedicated guide on this will follow soon), which typically provides the criteria for the acceptance of benefit and performance in the clinical evaluation. Additionally, SOTA analyses extend beyond clinical evidence, and include the identification of medical devices, applicable regulations, standards, and guidance. We will address these additional searches and reviews in the upcoming articles.

Another major misconception that affects the way companies conduct SOTA analyses—and ultimately their effectiveness—is the belief that SOTA analyses should be planned within the CEP. This is a common mistake, where searches are structured in the CEP and merely summarized in the CER. When done this way, the foundation for developing the CDP is missing. For example, without a proper SOTA analysis, it is impossible to define “an indicative list and specification of parameters to be used to determine, based on the state of the art in medicine, the acceptability of the benefit-risk ratio for the various indications and for the intended purpose or purposes of the device,” as required by MDR Annex XIV for the CEP.

In reality, the SOTA analysis serves as underpinning of a wide range of regulatory processes, including state of the art analyses, research and development, risk management, and post-market surveillance. It should, therefore, be planned before these processes start.

One notable—albeit very rare—exception is when the medical field cannot be identified through medical literature alone. In such cases, manufacturers would have to plan investigations to establish the clinical background within the CEP.

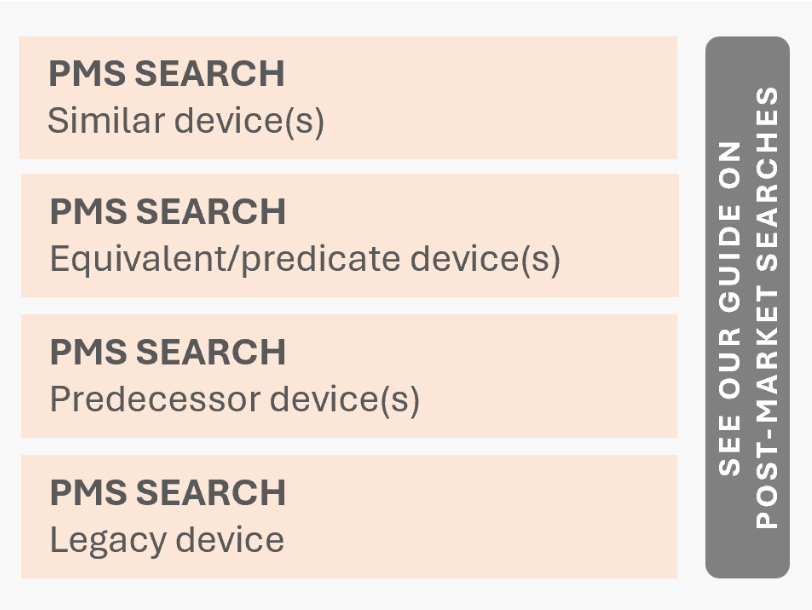

A final note: SOTA analyses are not the only systematic searches and reviews conducted in the pre-market phase (i.e., before receiving market access). Some systematic searches belong to PMCF and are carried out before certification, even though they are technically part of PMS. Before continuing, we encourage you to read about post-market searches, which are detailed in our guidance POST-MARKET SEARCHES. Medical background SOTA analyses are, in many ways, mirror approaches to post-market searches. Comparing the two frameworks helps understanding how to take decisions on planning, executing, documenting, and updating these searches. That is also the reason why at the end of chapter 2, we provide a side-by-side comparison of medical background SOTA analyses and post-market searches.

For example, consider a SOTA search on similar devices and a post-market search on the same subject how do you differentiate between them? A simple rule applies: SOTA searches and reviews never include a specific device trade name in their queries. If your search is focused on a particular device, it is almost certainly a post-market search. There is only one exception: when a specific device brand represents the state of the art in the medical field. That, however, is extremely rare.

1.2 Medical background

Now, let’s get to the core of the matter. This is where things become a bit more complex, but we can break it down step by step. This guide covers the first type of analysis in Figure 1.1: the medical background analysis. This analysis helps clinical reviewers understand the broader medical context in which your device operates, including its role, alternatives, and clinical relevance.

There are two types of medical background analyses:

• condition-focused and

• procedure-focused.

The first type—condition-focused—is aimed at device that are aimed at specific conditions. The term “condition” is not explicitly defined in regulatory guidance. However, it is widely used in medicine to describe a broad category of health issues, including diseases, injuries, disabilities, pathological processes. The second option applies when your device is intended to assist, enable, or perform a medical procedure, regardless of the underlying condition.Determining which type is needed for your device depends on whether its indication is condition-based or procedure-based. In version 3 of our guide on creating an intended purpose see INTENDED PURPOSE—we cover this distinction in detail. We strongly encourage reading that guide before proceeding. A condition-based medical background SOTA analysis systematically examines the current state of knowledge, clinical practices, and therapeutic approaches related to a specific medical condition. Instead of focusing on a single device or procedure, this analysis provides a comprehensive overview of all available alternatives for achieving the intended medical purpose. For example, if evaluating a device for diabetes diagnosis, the analysis would explore various diagnostic criteria and methods used for this condition.

A procedure-based medical background SOTA analysis, on the other hand, systematically examines the techniques and technologies used to perform a specific medical function. For instance, if the device under review is a thermometer, the analysis would cover all recognized methods of temperature measurement. At this stage, the SOTA analysis remains technology-agnostic, concentrating on the procedural category rather than individual technical alternatives. This means you are not yet investigating specific implementations (e.g., capillary vs. infrared thermometers). Instead, the goal is to identify alternative methods, emerging innovations and evidence-based best practices within the field. Similarly, analyzing the performance and safety characteristics of the identified alternatives is not yet required at this stage. This evaluation will be conducted in the next phase of the SOTA process, specifically during the meta analysis of identified medical alternatives (see Figure 1.1).

Finally, remember that if your device has

multiple indications—such as both the diagnosis and prevention of diabetes—you are expected to provide a medical background for each indication (diagnosis of diabetes and prevention of diabetes). Medical background analyses Post-market searches are systematic reviews. This means that they must be planned, conducted, reported, and updated according to best practices. Below, we outline these best practices.

Planning the search

This chapter outlines the key elements to consider when planning medical background SOTA analyses. These include defining objectives, selecting sources, developing a search strategy, and establishing appraisal criteria. For additional guidance on planning systematic searches and reviews, you may refer to the PRISMA 2020 statement.

We also encourage you to read about medical background SOTA analyses, which are detailed in our guidance SOTA_BACKGROUND. Post-market searches are, in many ways, mirror approaches to medical background SOTA analyses. Comparing the two frameworks helps understanding how to take decisions on planning, executing, documenting, and updating these searches. That is also the reason why at the end of this chapter we provide a side-by-side comparison of post-market searches and medical background SOTA analyses.

2.1 Evaluators

Specify who will perform the review. The definition of specific roles (such as author, reviewer, approver, etc.) typically depends on company specific procedures. The requirements of MEDDEV 2.7/1 concerning the expertise of clinical evaluators also applies to post-market searches. These requirements include knowledge of:

- research methodology (including clinical investigation and biostatistics);

- information management;

- regulatory requirements;

- medical writing;

- the device technology and its applications,

- diagnosis and management of the conditions intended to be diagnosed or managed by the device, knowledge of medical alternatives, treatment standards and technology.

In addition, evaluators must possess a relevant degree from higher education in the respective field and 5 years of documented professional experience, or 10 years of documented professional experience if a degree is not a prerequisite for the given task.

2.2 Review questions

As mentioned earlier, the goal of medical background SOTA analyses is to provide an objective, unbiased overview of standard medical practice related to a specific condition or procedure.

Relevant medical literature is systematically retrieved, and information is extracted from each source to address the specific review questions. These questions, which guide data extraction, are defined in the objectives section of the review plan. Table 2.1 summarizes these questions for a condition-based medical background SOTA analysis.

- Questions for condition-focused SOTAs

What is the definition of the condition? Coding: What are the specific codes for the con- dition in different medical coding systems (e.g., ICD-10, ICD-11, SNOMED)? Names: Are there other medical or commonly used names for the condition? Etiology: What is the cause or origin of the con- dition? Grading: Are there standardized grading sys- tems to classify or assess the severity of the condition? Epidemiology: What is the distribution, preva- lence, and incidence of the condition in different populations? Pathophysiology: What are the functional and biological changes caused by the condition? Medical alternatives: What are the available med- ical alternatives for performing the procedure? Which alternatives are considered outdated, standard of care, novel, first-in-line, second- in-line, supportive/adjuvant, or gold-standard? Which alternatives can be combined? Clinical presentation: What are the signs, symp- toms, and laboratory findings associated with the condition? Differential diagnosis: What other conditions could present similarly to this condition? Risk factors: What conditions, behaviors, or pre- disposing factors increase the likelihood of de- veloping this condition? Natural course: What is the expected progres- sion of the condition, with and without treat- ment? Prognosis: What is the anticipated outcome or long-term course of the condition? Complications: What are the possible complica- tions associated with the condition? Cultural and regional variations: How do presen- tation, treatment, and outcomes vary across dif- ferent populations and regions? Clinical outcomes and assessment tools: What are the key clinical outcomes and validated as- sessment tools used to evaluate the condition? Medical alternatives: What are the available medical alternatives available for (select based on your device purpose) preventing / predict- ing / prognosing / diagnosing / treating / etc. the condition? Which alternatives are consid- ered outdated, standard of care, novel, first-in- line, second-in-line, supportive/adjuvant, gold- standard? Which alternatives can be combined?

Table 2.1: List of typical questions concerning a condition to be answered in a medical background SOTA analysis.

Table 2.2 summarizes the questions concerning a procedure to be answered in a procedure focused medical background SOTA analysis.

2.3 Source selection

The objective of medical background reviews is to identify the highest-quality, evidence-based information from the most reliable and reputable sources the “cream” of the literature.

- Questions for procedure-focused SOTAs

Definition: What is the definition of the type of procedure? Names: Are there other medical or commonly used names for this type of procedure? Medical alternatives: What are the available med- ical alternatives for performing the procedure? Which alternatives are considered outdated, standard of care, novel, first-in-line, second- in-line, supportive/adjuvant, or gold-standard? Which alternatives can be combined?

Table 2.2: List of typical questions concerning a procedure to be answered in a medical background SOTA analysis.

- Example: Pelvimeter

- indication

A measuring device used to determine the pelvic dimensions [...]

Indeed, a pelvimeter helps healthcare providers determine whether the pelvic dimensions

are adequate for a vaginal delivery or if there might be complications that would necessitate a Cesarean section. Alternatively, the anatomy could be modified for esthetic

reasons:

- Example: Breast implant

- indication

A sterile implantable device designed to augment the breast [...]

Prediagnostic clinical picture

Devices intended for diagnosis are used with patients for whom the disease, injury, disability, or condition to be diagnosed has not yet manifested nor has been diagnosed. This means that for devices with diagnostic purposes, the clinical picture is prediagnostic:

it cannot include the specific disease, injury, or disability in question. Instead, the clinical picture must list the symptoms, signs, and factors that may potentially lead to these conditions. For example:

- Example: Polysomnogram

- indication

- clinical picture

A polysomnogram that can be used or at home or in-hospital for diagnosing of sleep apnea .

It is indicated for patients with symptoms such as loud snoring, gasping for air during sleep, awakening with a dry mouth, morning headache, difficulty staying asleep, daytime sleepiness, irritability [...]

The device is used to detect irregular breathing patterns during sleep that might indicate sleep apnea. Therefore, at the time the device is used, the patient cannot have a diagnosed sleep apnea condition yet. The clinical picture specifies sleep apnea’s symptoms

or risk factors (snoring, daytime sleepiness, etc.). Prediagnostic clinical pictures are not an exclusive of diagnostic devices but can also be the target of devices for prevention, prediction, monitoring and investigation. Let’s consider some examples:

- Example: CHA2DS2-VASc score calculator

- indication

- clinical picture

A software device indicated for the prediction of stroke.

It is indicated in patients with atrial fibrillation [...]

This software score calculator is indicated for the prediction of stroke. The device’s purpose is to prevent stroke from occurring. Therefore, at the time the device is used, the patient cannot have developed this condition yet. The clinical picture, instead, specifies another condition (atrial fibrillation) that must have been diagnosed in the patient before a user can utilize the device.

Postdiagnostic clinical picture

For purposes other than diagnosis, prevention, and prediciton, the clinical picture can be postdiagnostic. This implies that the subject has already received a diagnosis for a condition. In such cases, the clinical picture can provide additional insights into the condition. For instance, it might specify the severity or stage of the condition in more detail. Consider the following examples:

- Example: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy device

- indication

- clinical picture

A system for the treatment of kidney stones.

It can be used with patients with kidney stones of moderate size (smaller than 2 cm), and are located in the kidneys or the upper ureters. [...]

Multiple target populations

Like indications, a device can have several different target populations. The following example includes two distinct patient populations (treatment of psoriasis in adults and treatment of eczema in children):

- Example: Phototherapy device

- demographics

- clinical picture

A phototherapy device that emits UVB and UVA radiation. The device is indicated for the treatment of psoriasis and eczema. Specifically, the device is indicated for adult patients (maximum height 190 cm)

with moderate to severe psoriasis and for

pediatric patients (aged 6-17 years)

with eczema who have not responded adequately to conventional treatments. [...]

The two target populations will require separate considerations for certification (risk

management, clinical validation, post-market surveillance, etc.).

Contraindications and warnings

Contraindications can be though of as the “opposite” of the target population: they specify the demographics and clinical conditions of the patients for whom the device should not be used. For those familiar with clinical studies, this part of the intended purpose can be likened to the exclusion criteria of a clinical investigation.

Do not confuse contraindications and complications. Contraindications are conditions or factors that serve as reason not to use a medical device with a patient. Complications, on the other hand, are problems or side effects that arise during or after the treatment. Complications are detailed—together with the device risks and side-effects—in the instructions for use.

Consider an example:

- Example: Lung-cancer detection AI system

- indication

- contraindication

A software AI system intended to provide information which is used for the diagnosis lung cancer [...]

The device is not applicable for patients who have already undergone significant treatment (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy) as these treatments can alter the appearance of the tumor and surrounding tissues. [...]

In this case, the contraindications outline clinical factors that prevent the use of the device. However, there are situations where you must specify non clinical criteria for not using the device. These criteria are referred to as warnings. Let’s consider an example:

- Example: Glucose monitor

- indication

- warning

A continuous glucose monitoring system intended for use by individuals with diabetes to monitor blood glucose levels [...]

The device should not be used to measure glucose immediately after eating (immediate postprandial), as this may lead to innacurate readings. [...]

In this case, “immediate postprandial” is neither a demographics characteristic of the patient, nor a clinical condition. However, it is a factor that could affect the reliability of the device.

The intended purpose should only include warnings essential to the device’s application. It should not just list all warnings from the user manual.

Intended user(s)

In the intended purpose, you should provide two essential pieces of information concerning the user:

- State whether the user is a healthcare professional, a layperson, or both.

- State whether the patient is also a user.

If the patient is a user, the intended user must include lay users. Additionally, note that in most countries only healthcare professionals are allowed to emit diagnoses and prognoses. Devices intended to provide information that is used for diagnosis or prognosis

must include healthcare professionals as user. Additional information, such as the user’s type and level of education, and requirements

concerning device-specific training, should be provided separately in the instructions for use.

In the intended purpose, you only need to specify the users who utilize the device to achieve its medical purpose. It is not necessary to list all users, such as those involved in service, maintenance, and cleaning, as required by IEC 62366. Detailed specifications for these additional users can be provided in the instructions for use.

Relevant safety and performance information

Indications, target population, contraindications, warnings, and intended users are the essential pieces of information that must be specified for any device’s intended purpose. However, it is sometimes consigliabile to provide additional information relevant to understanding the device-specific application. If you feel uncertain about what to include, here is a tip: refer to the list of design-related requirements in Chapter II of MDR Annex I. If these GSPR highlight a specific characteristic, you should include this characteristic in the intended purpose. Below is a (non-exhaustive) list of characteristics to consider.

Invasiveness

State if the device is invasive (see MDR Article 2.6) or or surgically invasive (see MDR Annex VIII, Part 2.2).

Implant

State if the device is implantable (see MDR Article 2.5).

Personalization

State if the device is custom-made (see MDR Article 2.3). You can also specify whether the device is adaptable or patient-made according to the definition from IMDRF (see WG/N58) even though these terms are not directly defined in the MDR.

Microbial state status

State if the device is provided sterile.

Reusability

State if the device is single-use or reusable.

Substances

Devices incorporating or consisting of substances State whether the device incorporates or consists of:

- Medicinal products (including substances derived from human blood, or huma

plasma) - Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of human origin

- Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of animal origin

- Other non viable substances of biological origins (e.g., bacteria, fungi, viruses)

- Gases

- Latex

- Nanomaterials

- Substances which are carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic to reproduction

- Substances having endocrine-disrupting properties

- Other substances (specifies)

Absorbed and dispersed substances State whether the device is composed of substances (or combinations of substances) that are introduced into the body or applied to the skin, and that are absorbed by or locally dispersed in the body. These substances can include:

- Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of human origin

- Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of animal origin

- Other non viable substances of biological origins (e.g., bacteria, fungi, viruses)

- Gases

- Other substances (specify)

Administered substances State whether the device administers:

- Medicinal products (including substances derived from human blood, or huma

plasma) - Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of human origin

- Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of animal origin

- Other non viable substances of biological origins (e.g., bacteria, fungi, viruses)

- Gases

- Other substances (specifies)

Removed substances State whether the device removes any of the following substances from the body:

- Medicinal products (including substances derived from human blood, or huma

plasma) - Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of human origin

- Non-viable tissues or cells, or their derivatives, of animal origin

- Other non viable substances of biological origins (e.g., bacteria, fungi, viruses)

- Gases

- Other substances (specifies)

Radiation

State whether the device emits radiation for medical purposes and specify the radiation type (UVA, UVB, UVC, infrared, ionising, etc.).

Energy supplied to the patient

State whether the device supplies energy to the patient and specify the energy type (e.g., electrical, magnetic, mechanical, thermal, acoustic, etc.).

Power supply

State whether the device has an internal power supply and its type (e.g., disposable batteries, rechargeable batteries, etc.). State whether the device has an external power supply and its type (e.g., AC mains, DC, USB, wireless, etc.).

Compatibilities

Specify whether the device is intended for use in combination with other devices or equipment, or within a specific medical procedure.