- MDR-WET

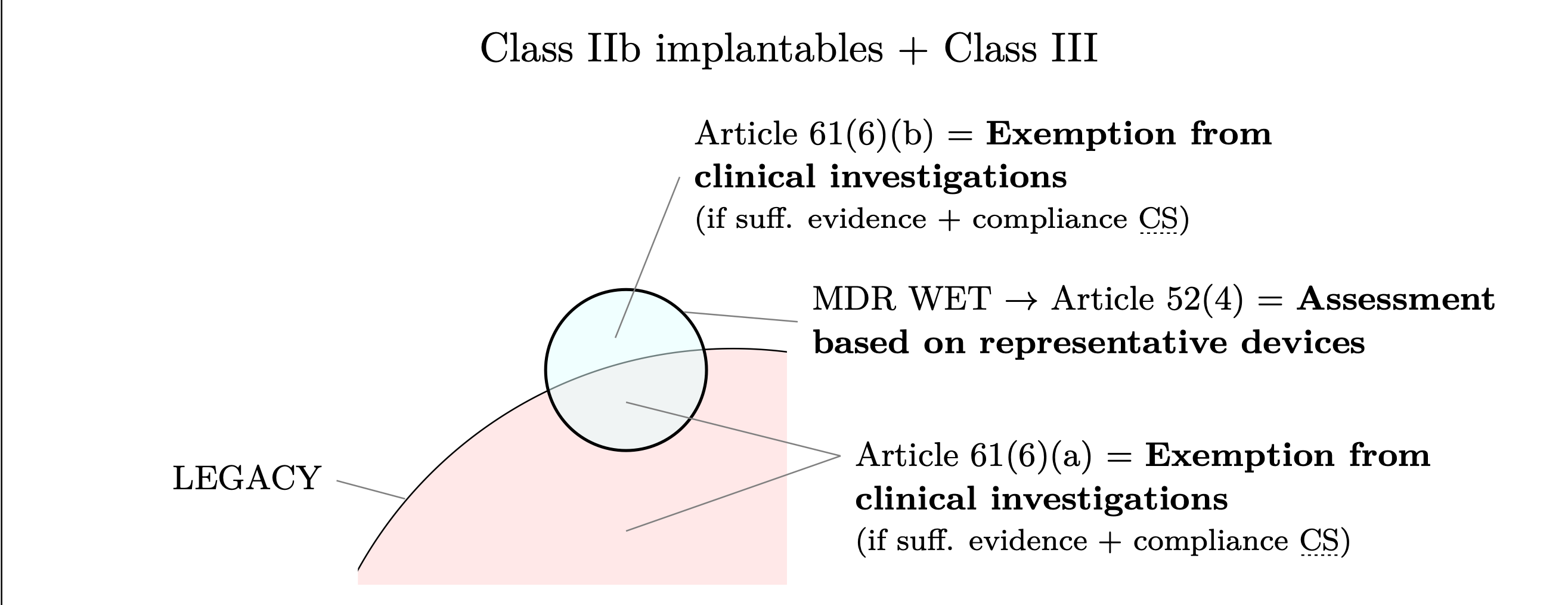

The MDR does not define what it means for a technology to be “well-established”. This is not an oversight. For the purposes of the regulation, a formal definition simply is unnecessary. Let’s see why. The expression Well-Established Technology (WET) appears in MDR Article 52(5) and Article 61(8). Here it is used in reference to the following class IIb implantable or class III devices: sutures, staples, dental fillings, dental braces, tooth crowns, screws, wedges, plates, wires, pins, clips, and connectors. These devices have been singled out by the European Commission for a more favorable regulatory treatment compared to other class IIb implantable or class III, Figure 1. The advantages include:

Assessment based on representative devices (Article 52(4)): For MDR–WET devices, the technical documentation does not need to be submitted and assessed individually for every device within a generic device group. Instead, a sample or representative device can be used to demonstrate conformity for the entire group. This significantly reduces the regulatory burden and accelerates the conformity assessment process.

Exemption from mandatory clinical investigations (Article 61(6)(b)): If the device qualifies as MDR–WET, the manufacturer may be exempt from conducting new clinical investigations, provided that sufficient clinical data already exist. This can lead to significant time and cost savings, particularly for implantable or Class III devices, where clinical investigations are otherwise extensive and resource-intensive.

Figure 1: Class IIb implantables and Class III devices that qualify as MDR–WET benefit from the exemptions

provided in MDR Article 52(4) (assessment based on representative devices) and Article 61(6)(b) (exemption

from mandatory clinical investigations). The figure also highlights that legacy devices may benefit from

Article 61(6)(a), which provides the same exemption from the requirement to conduct a clinical investigation

as Article 61(6)(b).

In the MDR the expression “well established”, therefore, does not explicitly imply any specific technological or clinical status. If we were to infer an MDR definition of well established technology–which we will refer to as MDR–WET–based solely on these two articles, it would essentially be limited to the following characteristics:

class IIb implantables or class III

explicitely selected by the European Commission

The MDR is also unequivocal on one point: The authority to amend the list of devices that benefit from the favorable treatment lies solely with the European Commission. In other words: Manufacturers of devices other than sutures, staples, dental fillings, dental braces, tooth crowns, screws, wedges, plates, wires, pins, clips, and connectors cannot currently invoke the favourable provisions that specifically reduce the certification burden for these designated devices specified in Article Articles 52(4) and 61(6)(b). Period.

If the MDR is clear on the matter, why did WET become such a hotly debated topic in the field? The controversy began with MDCG 2020-6.

2 MDCG–WET

In 2020, the Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) released guidance MDCG

2020-6 outlining a set of characteristics that it considers common to the products specif-

ically mentioned in the MDR—namely, sutures, staples, dental fillings, dental braces,

tooth crowns, screws, wedges, plates, wires, pins, clips, and connectors. According to

the MDCG, these characteristics are :

relatively simple, common and stable designs with little evolution;

their generic device group has well-known safety and has not been associated with safety issues in the past;

well-known clinical performance characteristics and their generic device group are standard of care devices where there is little evolution in indications and the state of the art;

a long history on the market.

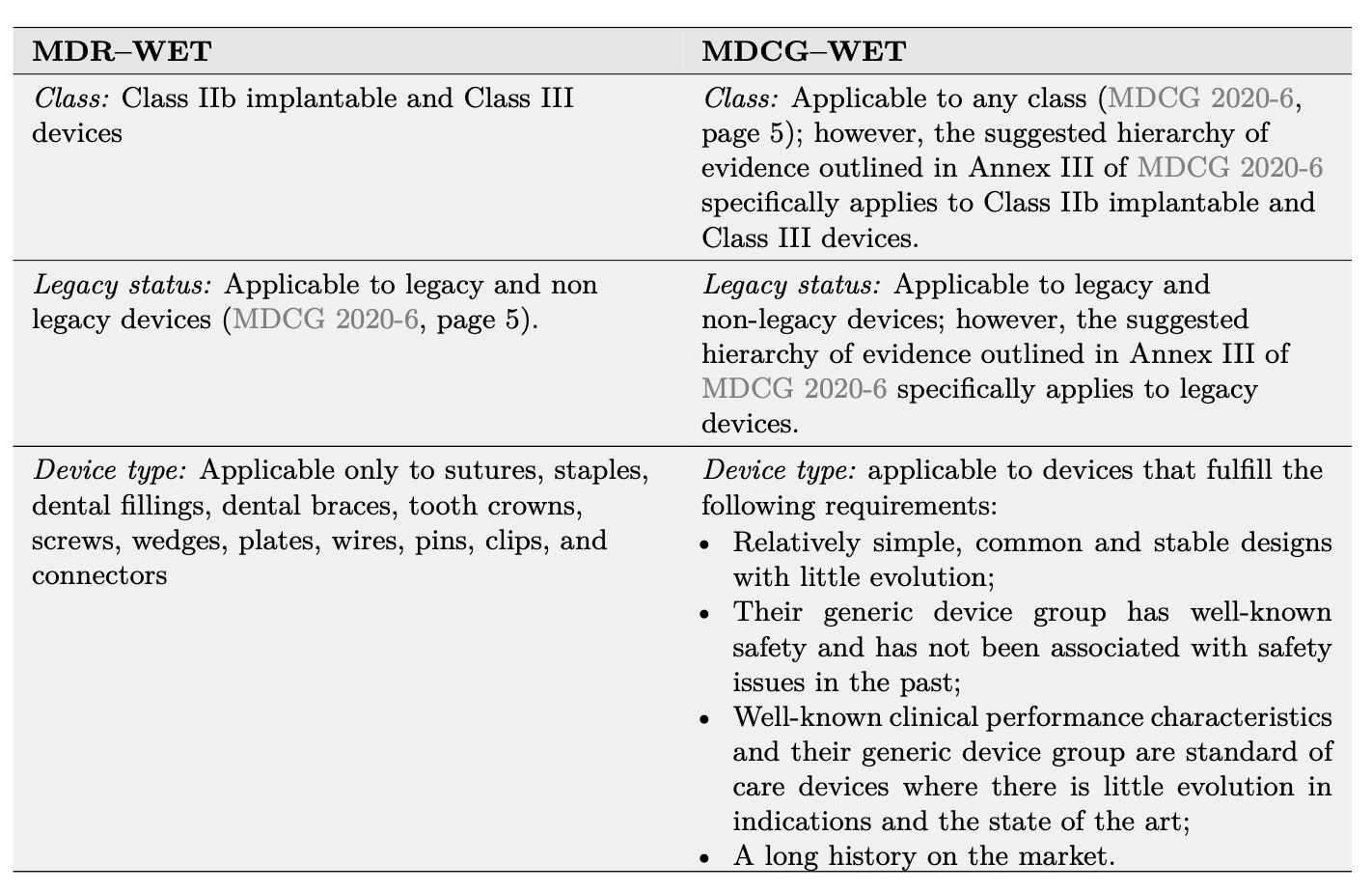

These properties define what we’ll refer to as an “MDCG–WET”. As highlighted in Table 1, the MDCG–WET definition strongly differs from the MDR–WET discussed in the previous section. Each of the four criteria in the MDCG-WET definition consists of multiple elements each of requirements which must be demonstrated separately. In Table 2 we illustrates these requirements and propose how to demonstrate MDCG–WET status using documents specific to the device under evaluation (device description, device history, vigilance

Table 1: Comparison between the MDR–WET and MDCG–WET definitions.

data), SOTA reviews and meta-analyses (medical background1, meta-analyses or umbrella reviews of device group performance and safety characteristics2), and post-market literature searches focusing on similar devices3. Below, we analyze how demonstrating MDCG–WET status affects the clinical evidence required for conformity assessment, according to MDCG 2020-6. First, MDCG 2020-6 focuses on legacy devices—that is, devices certified under MDD or AIMDD. Even if these legacy devices are not yet certified under the MDR, Article 120(3d) requires them to comply with the MDR’s post-market surveillance requirements. This means that legacy devices must have PMS data at their disposal—for example, complaints and vigilance data. According to the definition in Article 2(48) of the MDR, such PMS data qualify as “clinical data” and—as we know from Article 61(1)—clinical data form the basis for demonstrating conformity with the relevant GSPRs in the clinical evaluation. So does this mean that legacy devices automatically possess the data required for certification under the MDR? MDCG 2020-6 (pages 17 and 21) provides a clear answer to this question: regardless of the device type, complaints and vigilance data may only support other forms of clinical evidence—reliance on such data alone is not sufficient.