Introduction

Few parts of the MDR have sparked as much discussion as Rule 11. This is not surprising. Software fundamentally defies traditional methods of categorizing medical devices into established groups. Each software device is unique, impacting clinical decision-making in very specific ways. Indeed, the diverse nature of software devices was one of the main reasons behind the EU Commission’s decision to adopt the general safety and performance approach proposed by the IMDRF. This approach recognizes that nowadays it has become impossible to individually regulate each medical device group. Instead, common principles based on good scientific practices must be established that apply to all devices. Another issue is that, at the time of writing, Rule 11 effectively exists in two distinct forms. The first is the text of the rule itself and the interpretation provided by the MDCG. The second is how the rule is actually applied in the field. In principle, these two approaches should align. In practice, they do not. The reason is straightforward: implementing Rule 11 as intended represents a monumental shift for the medical technology field. Regulators are aware of this and have been cautious about pushing in the practice a change that could potentially stifle an expanding field. Achieving full application and a common understanding could take decades, similar to the pharmaceutical industry’s shift to evidence-based medicine 50 years ago. This discrepancy between theory and practice makes discussing Rule 11 challenging, as real-world applications often diverge significantly from theoretical intentions. For this reason, we have decided to divide this guidance into two parts. In Chapter 1, we explore the “theory” of Rule 11. We show that applying rule 11 means assessing the transfer of responsibility from healthcare professionals to standardized instructions that is, the software. The perspective provided in this first section is essentially where we anticipates the application of the rule to evolve over the next years. In Chapter 2, we analyze the “reality” of the application of Rule 11 on the market, providing practical tips and warnings with an eye to the future. Given the rapid changes in the field following the release of the MDR, what is standard practice today may soon be outdated.

Chapter 1

The theory

Rule 11 consists of three parts. The first part provides the general classification rules for software with diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The second part provides specific rules for the classification of software for monitoring of physiological process and vital physiological parameters. The third and final part stipulates that any devices not covered by the first two sections are classified as Class I. We will analyze each part separately.

1.1 Part 1

The first part of Rule 11 states Software intended to provide information which is used to take decisions with diagnosis or therapeutic purposes is classified as class IIa, except if such decisions have an impact that may cause: — death or an irreversible deterioration of a person’s state of health, in

which case it is in class III; or — a serious deterioration of a person’s state of health or a surgical intervention, in which case it is classified as class IIb. We break the analysis of this first part into three sections. First, we clarify what it means to provide information that is used to take decision. We then anylze diagnostic and therapeutic purposes covered by the MDR. Finaly, we analyze the two final exceptions specified in the two bullet points.

1.1.1 Information that is used to take decisions

The first part of MDR Annex VIII Rule 11 begins with the words “Software intended to provide information which is used to take decisions…”. These words highlights a crucial aspect of how medical device software works, namely by providing information to the user. Here we intentionally speak of “user”. In theory a machine could also make use of the output of medical software to take automated decision concerning patient management. In this case, however, MDR speaks of “closed loop systems”, the classification of which is covered in Rule 12.

Important : User vs. Patient

“User” and “patient” are distinct roles, not necessarily distinct people. Both roles can be covered by the same physical person. Consider, for example, an app that provides a physiotherapy excercises plan to the patient. In this case the patient is also a user. However, the opposite is also possible. Consider, for example, FFP3 masks. They are used by the healthcare professional, and protect the patient as well as the the healthcare professional from infection risk.

What does it mean that a software “provides information that is used to take decisions”? It means that the information provided by the software can influence patient management (see also box below). Why does this matter? In most countries, medical practice is strictly regulated. Only individuals who have undergone years of training can intervene in clinical decision-making. These professional doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, pharmacists, dentists, phychologists, radiologists, etc are tasked with the clinical management of patients. Software that impacts clinical decision-making takes on clinical responsibility—fully or partially—by encoding some of these medical tasks into a set of instructions1. Similarly to how governments require healthcare professionals to undergo necessary training to manage medical responsibilities, they also require that software assuming medical responsibility meets specific requirements.

Important : Patient management

It will be obvious to most, but it is worth emphasizing this point to avoid misunderstanding. When the MDR refers to “patient management,” it does not refer to managing patient data for administrative purposes. Instead, “patient management” means the comprehensive coordination and oversight of a patient’s clinical care, which includes diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.

Before analyzing how software influences clinical decision-making, let’s examine two examples of software that do not affect clinical decision-making. Consider a software application that enables patients to remotely discuss their symptoms with their doctor to determine if they need to stay home from work for medical reasons. During the call, the doctor performs a clinical evaluation (anamnesis), assesses the symptoms as consistent with the flu, and decides that an in-person visit is unnecessary. The doctor then issues a digital medical excuse for work absence and schedules a follow-up consultation. In this scenario, the software solely facilitates communication and does not engage in any medical decision-making. All critical decisions—from conducting the anamnesis to determining the necessity of follow-up visits are made by the licensed healthcare professional. This software provides a platform for a conversation like the one that could otherwise take place in the doctor’s office.

Important : Telemedicine

As we will explore below, just because software is classified as “telemedicine” does not mean it cannot influence clinical decisions. Consider the previous example, where the consultation involves inspecting a patient’s skin using a camera image. An inaccurate image could lead the practitioner to make an incorrect clinical decision. If the software allows this kind of application, it becomes the manufacturer’s responsibility to ensure that the images collected by the softare is suitable for diagnostic purposes.

Consider another example: A software that enables doctors to digitally collect and store

clinical data. The doctor conducts the anamnesis and stores this alphanumeric data in a database for later retrieval in its original form. The software does not modify or process the data; it merely stores them for later retrieval, effectively replacing traditional paper records. In this scenario, the software does not assume any medical responsibility nordoes it perform any medical decision-making functions; it simply facilitates data storage. Every decision—what information to collect, how to interpret it—is made by the licensed healthcare professional.

Important : Storage and retrieval

When MDCG 2019-11 specifies that storage and retrieval do not constitue medical purpose it refers to the technical action of storing and retrieving the data. The MDCG is not referring to the action of deciding what must stored or retrieved. See also the section on cinical input below.

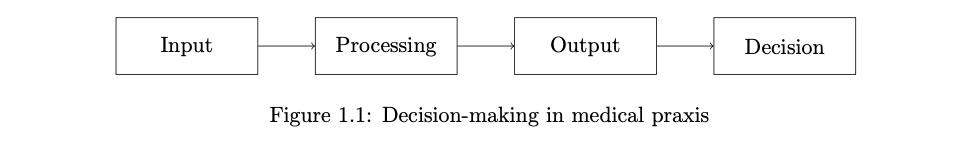

To analyze how software can influence clinical decision-making, we examine the workflow depicted in Figure 1.1. In traditional clinical decision-making, healthcare professionals start by collecting clinical information from patients (input). They then analyze this data to discern key details and patterns (processing). To understand the output phase, consider a healthcare professional who seeks additional insights from a colleague’s expertise. This professional communicates their findings using values, words, texts, and visuals. The final phase (decision) involves the actual decision-making process, where the professional determines the diagnosis and treatment plan for the patient. In the remainder of this section, we explore how software can impact each step in this chain.

Continue reading

Download the full document for FREE!

Explore the complete article: How to use MDR Rule 11 for FREE!